The disappearance of American pilot Amelia Earhart while flying over the Pacific Ocean during a 1937 flight around the world became aviation’s greatest enduring mystery.

81 years after her disappearance during a flight over the massive Pacific Ocean, while attempting to circumnavigate the globe, the legend endures. Yet many historians believe that not only was the American icon an overrated pilot, but she wasn’t in the same class as some of the other female pilots in the early days of aviation.

Her first headline came in 1928, when Earhart became the first woman to cross the Atlantic in a plane — though she rode shotgun. (Pilot Bill Stultz and Slim Gordon, the mechanic, had done the actual flying.) No matter: Earhart was hailed as “Lady Lindy” by a fawning press and adoring crowds.

Between 1930 and 1935, Earhart had set seven women’s speed and distance aviation records in a variety of aircraft, including the Kinner Airster, Lockheed Vega and Pitcairn Autogyro.

She also wrote several best-selling books about her flying experiences and was instrumental in forming The Ninety-Nines, an organisation for female pilots.

There were other outstanding women pilots of her day. While she was dining with Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt at the White House, this group of pioneer female pilots were racking up truly incredible achievements. Elinor Smith set out on a solo flight in 1926, at the age of 15. Three years later, she set two endurance records and the women’s world speed record. In the 30s, she would find her way to Hollywood, where she worked as a stunt pilot in movies.

In 1932, Earhart struck out on her own, flying across the Atlantic — the first woman and the second person, five years after Charles Lindbergh, to make the trip.

Louise Thaden set the world’s altitude record for women, flying above 20,000 feet. In 1936, the year before Earhart’s final flight, she bested all the men in the Bendix Transcontinental Air Race.

ON THIS DAY in 1935, Amelia set a record by becoming the first male or female aviator to fly solo from Hawaii to the US mainland.

She departed the state’s capital Honolulu and landed in Oakland, California.

At the time, the transoceanic flight had been attempted by many others, including three unlucky competitors in the deadly Dole Air Race in 1927.

But Earhart made it look easy.

Her trailblazing flight went smoothly, with no mechanical breakdowns.

In her final hours, she was so relaxed that she listened to the broadcast of the Metropolitan Opera from New York.

Tragically, Earhart’s incredible life was cut short in mysterious circumstances.

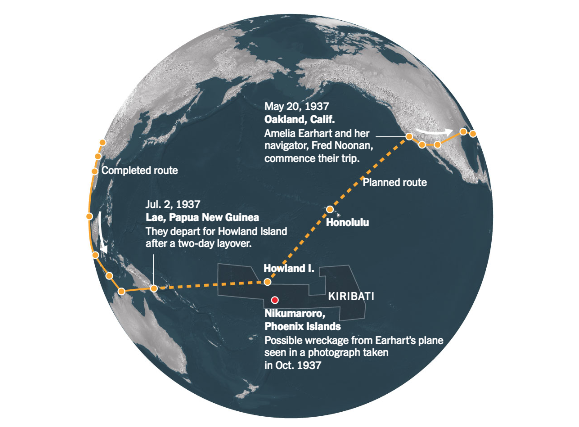

In 1937, Earhart and navigator Fred Noonan set out to circumnavigate the equator. Had they succeeded, Earhart would have landed in the record books. (Other pilots had circled the globe, but used shorter routes.)

On July 2nd, the pair were on the most difficult part of their journey — attempting to fly from New Guinea to tiny Howland Island, some 2,500 away — when they lost radio contact with the U.S. Coast Guard.

Nearly one year and six months after the disappearance, Earhart was officially declared dead.

To this day, more than 80 years later, investigations continue, and the mystery remains of significant public interest. Historians and aviation experts believe that Earhart didn’t fully understand her radio equipment which could have played a big part in their disappearance.

HER FIRST FLIGHT WAS UNUSUAL

At age seven, growing up in Kansas, she roped in her uncle to help make a homemade rollercoaster. After crashing it, she told her sister Grace it “was just like flying.” But when she saw one of the Wright brothers’ first planes at the Iowa State Fair in 1908 she was underwhelmed.

In Last Flight, a collections of her diary entries published after her death, Earhart called the aircraft “a thing of rusty wire and wood.” She first got on a plane, as a passenger, in 1920.

HER FIRST FLYING INSTRUCTOR WAS ANOTHER WOMAN

Neta Snook, the first woman to run her own aviation business and commercial airfield, gave Earhart flying lessons near Long Beach, California in 1921. Snook reportedly charged $1 in Liberty Bonds for every minute they spent in the air.

To pay for flying lessons, Earhart worked in a photography studio and as a filing clerk at the Los Angeles Telephone Company; other jobs included nurses’ aid and social worker.

HER FIRST PLANE WAS A LEMON

Within six months of her first lesson, Earhart paid $2000 for her first plane, named The Canary. The second-hand yellow Kinner Airster biplane was the second one ever built. Snook told her it was underpowered, overpriced, and tough for a beginner to land.

HER ADVENTUROUS SPIRIT CAME FROM HER MOTHER

Amy Earhart was the first woman to climb Pikes Peak in Colorado. She encouraged her daughter’s passion for flying, using an inheritance to pay for The Canary. But Amelia’s father was afraid of flying.

She believed in pre-nups

Earhart met promoter George Putnam when he offered to help her write a book. Their creative collaboration led to love, but when he proposed Amelia reportedly suggested a trial marriage for a year because she was worried about losing independence.

Their marriage lasted until her disappearance, with Putnam organising his wife’s press tours and endorsements, including a line for the Baltimore Luggage Company that was produced from 1933 until the 1970s.

SHE WROTE FOR COSMOPOLITAN

The same year she met Putnam, Earhart landed the job of Cosmopolitan’s aviation editor. She had 16 stories published including “Shall You Let Your Daughter Fly?” and “Why Are Women Afraid to Fly?”

She was the first woman to fly the Atlantic solo

After crossing the Atlantic in 1928 as a passenger, she flew from Newfoundland to Ireland four years later. In June 1928, she made the crossing in 14 hours, landing in a cow paddock in Londonderry, Northern Ireland. When a farmer found her and plane and asked where she was from, he was reluctant to believe her.

HER OWN FASHION LABEL

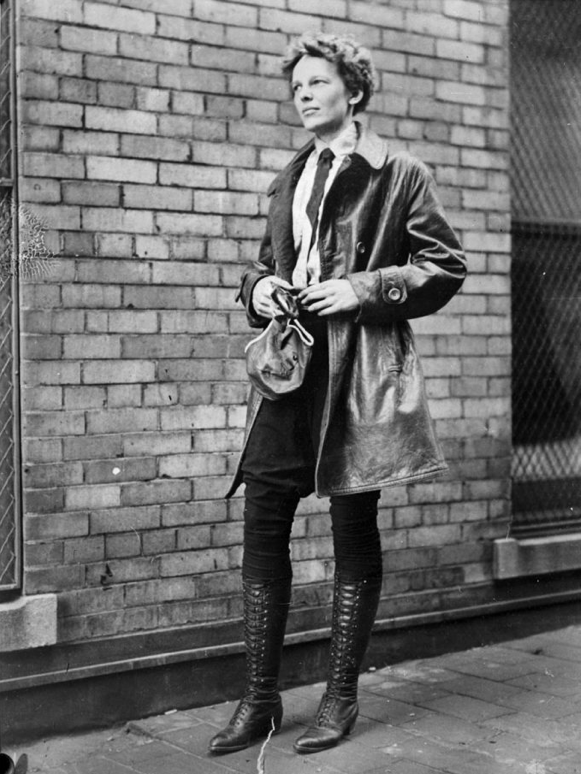

While the most famous photos show Earhart in a leather bomber jacket and men’s pants, she loved fashion and was encouraged to design a collection after hosting a lunch for Italian designer Elsa Schiaparelli. In 1934 the Amelia Earhart line was launched in one department store in 30 major cities. Parachute silks were used in the clothes, which featured propeller-shaped buttons, belts made from parachute cords and fasteners made from actual wing bolts.

RECOGNIZED THE NEED FOR SUPPORT AND MENTORSHIP

Earhart was the first president of the Ninety-Nines, a society of 99 female aviators. She sponsored a ‘Hat of the Month’ club which awarded a Stetson to the Ninety-Nine who flew into the most airports each month.

Amelia was a great American, brave, daring, and like the other female pilots of the day, not prepared to just be locked in a kitchen. Her achievements and fame have lived on for almost one-hundred years.